Architectural Profiling is a technique used to understand the relative complexity of different areas of concern for an architecture.

Architecture addresses a number of concerns within a system and so a useful early approach is to consider the profile of the architecture in terms of the relative complexity of each of these areas. This helps to give a feel for the shape of the requirements, architecture and overall solution. We can also identify possible areas in which we can reuse existing components, frameworks or maybe standard packages of requirements, components and tests (e.g. serverless applications or cloud templates). Architectural profiles may be useful at any level of architecture (Enterprise, Solution and System) and are useful to understand areas of complexity in the requirements space, especially for understanding the relative complexity of non-functionals.

We consider a number of “dimensions” representing the various concerns of architecture. Starting with the FURPS scale (Funtionality, Usability, Reliability, Perforamce and Supportability), but also considering other important dimensions such as security or cost-optimisation we extend the model in whatever meaningful way is necessary. The dimensions used aren’t set in stone, we use the dimensions that are meaningful for the organization and type of project.

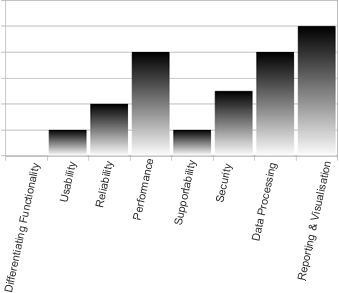

Here’s an example profile of an application that does some significant data processing, needs to do it reasonably quickly but not excessively so and has got to do some pretty visualizations of the data. Other than that it’s fairly straight forward. Initially we’ll discuss the non-functional aspects.

The x-axis here is close to the standard FURPS scale with a couple of extra dimensions - as mentioned above we might customize the dimensions to the context of the project or organization.

The y-axis ranges from simple to high complexity but it is deliberately not labeled (not something we’d normally recommend!) so we can focus on the relative complexity of these dimensions of the requirements, quality, architecture and therefore solution. Adding false accuracy of scale is not worthwhile.

The height of one of these bars helps us shape the architectural approach that the work needs, including how implicit or explicit the architecture and documentation needs to be.

For example, let’s take the security dimension and consider it from simple, complicated and complex.

If it’s empty/simple we know that we don’t need users, audit logs etc. Maybe we just need a user session for personalization but we could pick that up from the browser or OS.

If it’s medium/complicated, like it is in this example, we know that we’re probably going to some user stories around:

- logging in

- changing password

- managing users

- managing permissions

- checking permissions

In most organizations, and for most developers, these are very common requirements which have been implemented many times. There is unlikely to be a need to do detailed requirements documentation, design or even significant testing as the quality risk is likely to be low. Hopefully we will be able to simply use a Cloud managed service or common corporate authentication and authorization mechanisms, so we may not have to implement any of this stuff directly. Of course just because quality risks are likely to be low doesn’t mean we can assume there are no bugs, a minimal level of testing might still be required.

If the bar for security is higher/complex up then we might need to consider elements such as fine grained security, overlapping groups, encryption, auditing, digital signing, federated user data stores, legal compliance, information assurance, biometric identification, multi-factor authentication, etc. Cloud Services can often play into many of these spaces but few cloud services can currently support all of these requirements directly.

If the bar for security is at the very top, then we are in a high complexity security context. In this case we may be dealing with an unstable cyber security situation such as needing to operate securely in a hostile environment where adversaries are actively trying to compromise our software or operational effectiveness. These situations are not resolved through just up-front design, but through architecting for change, experimentation and learning.

Other Dimensions

As well as the standard non-functional “URPS+” dimensions a common aspect is “Data Processing” which covers the volume and shape of data a system might need to deal with. Simple entity management is typically fairly low, whereas running significant algorithms across that data will push the bar up. Large datasets start to bring in some elasticity and cost concerns, “Big Data” and massively parallelized processing will push the bar up further.

For lower levels of complexity, dealing with simple entity creation, editing and deletion we do not recommend elaborating textual requirements or CRUD stories/simplistic scenarios, similarly we do not recommend creating a lot of designdiagrams that describe CRUD operations for each entity. However a simple persistency mechanism and data model are frequently worthwhile.

Another dimension we frequently use for user facing systems is “Reporting and Visualization” means graphical rendering of data or processing. At its simplest level this dimension can be simple GUI feedback but it can range to interactive touch displays, augmented reality, VR etc. As the bar increases, the requirement for User Experience (UX) practices increases.

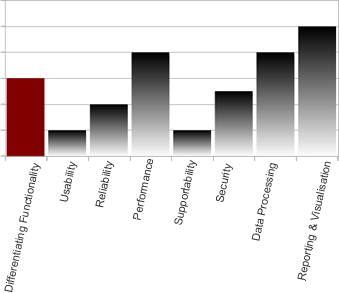

The Functional Dimension

The first dimension we title “Differentiating Functionality” which represents the functional requirements which make the product unique. If this bar is low then the product is likely to be a commodity offering rather than a market differentiating product, in which case there should be a strong strategic reason to buy not build. A significant non-functional difference between the proposed product and existing alternatives may be a perfectly valid reason, but we recommend making that explicitly visible.

If, during product evolution, this bar lowers significantly then the product should be considered for retirement or replacement with a commodity solution. Sometimes market disruption will out-move a business in which case cutting losses, and redirecting onto more differentiating business value, is a sensible business decision.

Other than these cases, the functional dimension is typically the source of business value and so is often prioritized by customers and users above the other dimensions. Using an architectural profile is a useful way of balancing the requirements and development work to consider the whole problem. We tend to use a different color for the functional bar to help draw out this distinction and ensure a realistic balance of concerns.

Technical risks, and likely quality risks, will be hiding in any dimension with a high complexity and so will be fertile ground for finding fringe cases. Complex areas are excellent candidates for early iterative development as their implementation can help to de-risk project, programmes and portfolios.

The use of managed Cloud services in high complexity areas can help to reduce complexity, however often at the expense of trading configurability or other non-functional aspects. This can be beneficial or negative depending on your specific context.

Edit this page