“Architecture” is often hard to define as the term is used to describe many facets of structure, behavior, design, activity and documentation. The concept of architecture is also relevant at different levels of an IT system as the components of one system become a reusable platform for the next system. Ultimately the emergent behavior caused by layers of architectural dependencies and reuse can be difficult to predict.

Architecture is a high level view of a system in the context of its environment, dependencies and technology. Architecture describes structure, behavior, integration and aesthetics.

Architecture must be solid, useful and beautiful.

Architecture is concerned with explaining the structure, behavior, integration and aesthetics of a system (or system of systems). It explains common ways of doing things (patterns and mechanisms), how Non-Functional and Functional requirements are met, technology choices, how systems are put together and provides a common technical direction for teams working with them. Architecture provides a shape, and look and feel, to the internals of a system that are the foundation for the ultimate external behavior.

The idea of an “Architect” with responisbility across such a broad focus is analogous to that of a structural architect concerned with buildings. Indeed, in 25 BCE Vitruvius (a well known Roman writer and architect who inspired Leonardo Da Vinci, hence the Vitruvian Man) described an architect as:

The ideal architect should be a [person] of letters, a mathematician, familiar with historical studies, a diligent of philosophy, acquainted with music, not ignorant of medicine, learned in the responses of jurisconsults, familiar with astronomy and astronomical calculations.

Vitruvius is famous for stating that architecture must be solid, useful, beautiful (De architectura). The same three qualities relate to software architecture. Despite architecture being a fine balance between a subtle science and an exact art we must realize it is only useful if it is aligned to requirements and becomes executable.

Good architecture speeds you up in building some software. Bad architecture is lots of diagrams and documents.

Architecture, not documentation

Modern software development values working software in the form of quality releases from short development cycles over comprehensive documentation, business analysis and enterprise architecture documentation. Choosing how much architectural work is necessary up-front, and how much architectural documentation is necessary, is difficult. The amount of documentation you need to solve a problem is often less than you need to explain it to others.

Traditional document-focused development methods promoted large up-front effort to detail the architecture and system design prior to development, usually in document or model form. As well as the inherent late risk mitigation issues in waterfall processes this could often cause “analysis paralysis” where architectural work was seen as an endless diagram drawing exercise.

Agile and iterative methods have focused on working software over documents and designs, however this doesn’t mean that no documents or designs should be produced. It is almost always useful to have some description of an architecture before and after development, even if it’s just a statement that the team’s usual architecture is used.

Good architecture addresses how we’ll resolve the major technical risks, communicates between the team the overall structure of the solution and works out how our solution will meet the functional and non-functional requirements. Knowing when we’ve worked out enough architecture so that we’ve reduced the complexity of the problem into manageable sizes for a team is a difficult challenge.

Doing too much architectural analysis or elaboration, either through abstract design and modelling, or practical spiking (writing small amounts of throwaway code to demonstrate the feasibility of a technical approach or architectural idea) will slow down a development project and increase the risk of wasted work. Value is only achieved once working systems are in the hands of the customers/users.

Alternatively, not doing enough architectural analysis can lead to significant architectural refactoring during a projects lifetime, as key requirements can’t be met based on the current architecture, again leading to wasted work and slowing down the project.

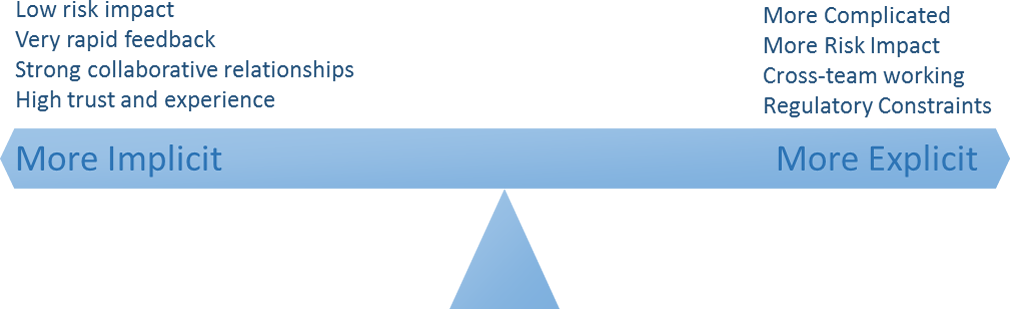

Architectural work, and corresponding documentation can be more implicit when complexity is low, rapid feedback is working and there are strong, high trust, relationships. Architectural analysis and documentation need to be more explicit when work is more complicated, where risk is higher and where there are more cross-team or distributed communication concerns.

High complexity architecture, in contrast, is often subject to a lot of change. Up front work on structure and behavior is prone to extensive rework, and although we do not recommend completely emergent architecture, in these situations managing for emergent structure and behavior by architecting for change becomes the best way to succeed.

When doing up front architecture, especially in the form of documents and models, we need to be careful to consider architectural work in the context of the team’s definition of done. Typical levels of done don’t normally include “analysed”, “architected” or “designed”. Although these terms might be meaningful to describe internal team development states they do not constitute working software and are only a step on the way to creating value.

Architectural models and documentation do not constitute progress. Good architecture is working software, and that’s progress.

Levels of Architecture?

Architecture can be thought of in three levels:

- Enterprise Architecture applies architecture principles and practices to guide organizations through the business, information, process, and technology changes necessary to execute their strategies

- Solution Architecture applies architecture principles and practices, addressing structure, behavior and aesthetics, to a related set of products (or system-of-systems) that collectively generate business value through their end-to-end use. Solution architecture focuses on integration and behaviour.

- System Architecture applies architecture principles and practices to a particular software system focusing on structure and behavior to address functional and non-functional requirements (usability, reliability, performance and scalability etc.).

How does Cloud change Architecture?

Traditional architecture practices are there to reduce risk. Often that risk is simply the cost of being wrong. That cost was often in infrastructure, servers and software. Because Cloud Computing makes all of things temporary, the cost of being wrong, and trying something new is greatly reduced. When it can take just a few hours to create a large set of infrastructure to try and idea, it’s more expensive to have a half-day meeting about a problem than to simply try it and throw it away afterwards, only paying for the temporary resources used to prove something.

Cloud Computing changes how we approach architecture because the cost when we get things wrong is reduced. That means that architecture practices with cloud are more focussed on experimentation, empiricism and spiking. Because structure and scaling can be changed dynamically, Cloud architectures are typically focussed on the flow of data, rather than the structure and deployment of a solution. As a result cloud architecture diagrams are typically structured in a left to right format describing data moving between high-order services rather than the traditional top-down structural component or class diagrams.

Edit this page